Drafting The Blueprint For AI At Columbia Engineering

In this conversation, Dean Shih-Fu Chang and Vice Dean Vishal Misra discuss how the School is driving and responding to this exciting moment in the development of artificial intelligence.

In this conversation, Dean Shih-Fu Chang and Vice Dean Vishal Misra discuss how the School is driving and responding to this exciting moment in the development of artificial intelligence.

Professor Vishal Misra talks ChatGPT, AI and ethics, and more as the School’s newly appointed—and first—head of AI and Computing.

ChatGPT and other bots have revived conversations on artificial general intelligence. Scientists say algorithms won’t surpass you any time soon.

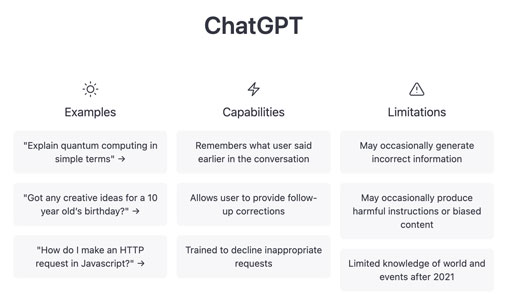

OpenAI’s ChatGPT is an artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot that is trained to follow the instruction in a prompt and give a detailed response. It is built upon GPT-3, a type of large language model (LLM) that predicts and generates text. Given a sequence of words, it will predict the word that has the highest probability of following next (kind of like autocomplete). These models are trained on huge datasets that allow them to generate answers to questions. ChatGPT works quickly and gives answers within seconds, and it also learns from every interaction and improves daily.

It can create a letter to your super asking for a repair to be done, write code and fix bugs, and suggest plot summaries for novels. But that does not mean that it is perfect. The problem with LLMs is that they can “hallucinate” and make things up. ChatGPT is guilty of this; some of the answers in its outputs do not even exist. It is also not trained to be truthful and it answers queries with a lot of confidence and authority, which is worrisome.

It is being compared to the last great tech disruption–the internet’s onset in the 1990s. We asked CS professors what the technology could do and how to use the tool the right way.

Vishal Misra

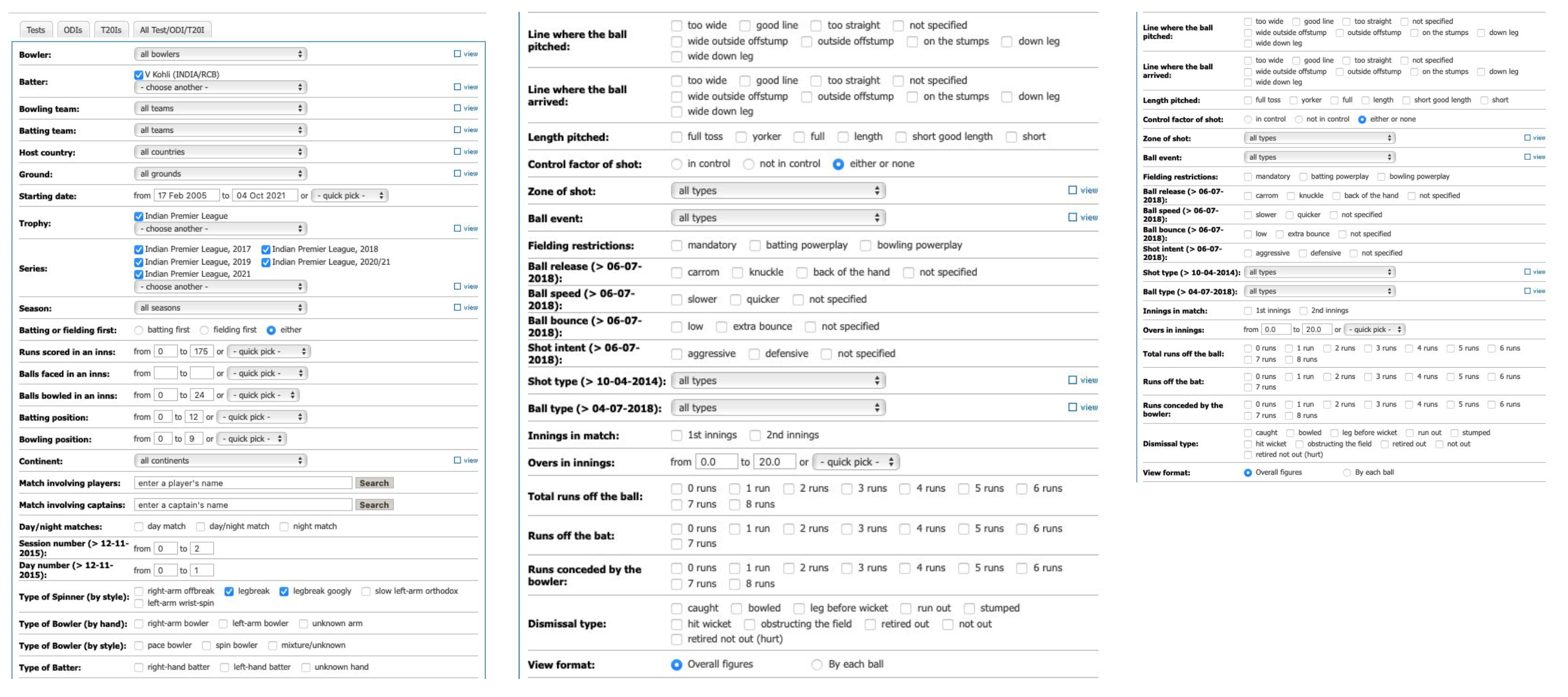

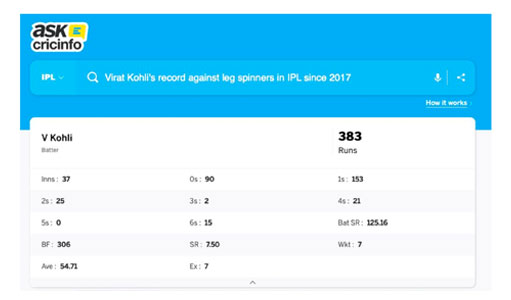

I have been using GPT-3 for over two years now. It is the underlying model behind my cricket search app for ESPN.

The original interface was cumbersome and needed an analyst who could use specialized programming languages to access the answer.

We developed AskCricInfo, which takes human input–questions or search queries–and converts the queries into a structured language like SQL that machines understand. The technology can “translate” the question into a programming language, find the answer, and quickly send it back to the user.

It is an excellent example of the power of underlying technology and what the tool can do. ChatGPT is very interesting. It is the first chatbot that makes “intelligent” and engaging conversations. There are definite use cases for making it a very effective teaching tool. It is up to the instructors to imagine a world where something like ChatGPT will always be available and teach students how to use it effectively. A lot can go wrong with ChatGPT- primarily because of its design that makes it bullshit confidently. But that is a problem with all LLMs, not just ChatGPT.

Kathy McKeown

ChatGPT and the technology it is built on, GPT3, are game changers. With them and the other large language models that have recently emerged, models can now produce extremely fluent text. They are also able to perform a variety of tasks in a way that was not previously possible. And there are many situations in which they can be used to help us do things that we previously found tedious. But they are not able to do as much as we might initially have imagined. They have limitations that are not always immediately obvious, and researchers are taking the time to study them so that we can accurately characterize what they can and cannot do. Nonetheless, they change how we do research in the natural language field and how we build new models to carry out other tasks.

I think we need to learn how to incorporate them into our teaching because they are here to stay. Students know about them and will know how to use them. We will need to think creatively about how to teach students what these tools do well and what they do poorly, when they can be used as a tool to aid in research, and situations in which it would be dishonest. I imagine situations where we ask ChatGPT to answer an essay question, ask the student to critique the essay and identify what it does poorly, and then ask the student to write an essay that goes beyond what ChatGPT can do.

The worst problem with ChatGPT is that it is not always truthful. In fact, it may often lie or hallucinate facts. It does this very fluently, making its lies sound very plausible. This is quite a barrier to use in a real-world situation unless it is used by someone who knows what is correct, what is not, and can sift the good from the bad. Technology constantly changes, though, and it is a problem that researchers are actively working on.

Itsik Pe’er

I asked ChatGPT about AI language models, and this is the output:

AI language models like ChatGPT, its competitors and successors represent a significant advancement in the field of Natural Language Processing (NLP). These models have the ability to generate human-like text based on a massive amount of input data, making them useful for various applications such as chatbots, question-answering systems, and content generation.

However, it is important to note that despite their sophisticated capabilities, they still have limitations and may generate outputs that are inaccurate, biased, or inappropriate. It is crucial to ensure responsible development and deployment of these models to maximize their benefits while minimizing potential harm.

The above demonstrates my thoughts more than I could otherwise express. In particular: it is already useful, but often not out-of-the-box, but I am a techno-optimist and believe even more usefulness is coming.

As a former judge in high school debate competitions, it reminds me of the most eloquent contestants, who would, if they needed to, lie through their teeth without missing a heartbeat. For instance, in response to this prompt, “What could go wrong with tools like ChatGPT?”, it writes:

There are several potential risks associated with the use of AI language models like ChatGPT:

Bias: AI models are trained on large amounts of text data, which may reflect societal biases and lead to biased outputs.

Misinformation: AI models may generate false or misleading information, which could have serious consequences if relied upon.

Privacy Concerns: AI models process large amounts of personal information, raising privacy and security concerns.

Misuse: AI models may be used for malicious purposes, such as spreading hate speech, fake news, or conducting phishing attacks.

Job Loss: AI models may automate certain tasks, leading to job loss in industries that rely on those tasks.

Therefore, it is important to carefully consider the potential risks and consequences of AI models and to develop and deploy them responsibly to minimize potential harm.

These are all valid points, but more context needs to be considered:

Misra’s “Ask Here First” offers easy data access for all users and can be applied to any data-rich field, from sports and e-commerce to investment banking.

Imagine a world of rapid and effective emergency response that takes advantage of the latest in cutting-edge technology.

A data-driven approach to predict outcomes of everything from sports games, business profitability, and public policies.

Professor Vishal Misra is an avid fan of cricket and now works on research that looks at the vast amount of data on the sport.

“I live in two worlds – one where I am a computer science professor and the other where I am ‘the cricket guy’,” said Vishal Misra, who has been with the department since 2001 and recently received the Distinguished Alumnus of IIT Bombay award.

For the most part, Misra has kept these two worlds separate until last year when he worked on research with colleagues at MIT that forecasts the evolution or progress of the score of a cricket match.

When a game is affected by rain and is cut short, there is a statistical system in place – the Duckworth-Lewis-Stern System which either resets the target or declares the winner if no more play is possible. Their analysis showed that the current method is biased and they developed a better method based on the same ideas that are used to predict the evolution of the game. Their algorithm looks at data of past games and the current game and uses the theory of robust synthetic control to come up with a prediction that is surprisingly accurate.

The first time Misra became involved in the techie side of cricket was through CricInfo, the go-to website for anything to do with the sport. (It is now owned by ESPN.)

In the early 90s, during the internet’s infancy, fans would “meet” and chat in IRC (internet relay chat) chat rooms to talk about the sport. This was a godsend for Misra who had moved to the United States from India for graduate studies at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Cricket was (and still is) not that popular here but imagine living in 1993 and not be able to hop onto a computer or a smartphone to find out the latest scores? He would call home or go to a bookstore in Boston to buy Indian sports magazines like Sportstar and India Today.

Through the #cricket chatrooms, he met CricInfo’s founder Simon King and they developed the first website with the help of other volunteers spread across the globe. Misra shared, “It was a site by the fans for the fans, that was always the priority.” They also launched live scorecards and game coverage of the 1996 world championships. Misra wrote about the experience for CricInfo’s 20th anniversary. He stuck with his PhD studies and remained in the US when CricInfo became a proper business and opened an office in England.

“I did a lot of coding back then but my first computer science class was the one I taught here in Columbia,” said Misra, who studied electrical engineering for his undergraduate and graduate degrees and joined the department as an assistant professor.

For his PhD thesis, he developed a stochastic differential equation model for TCP, the protocol that carries almost all of the internet’s data traffic. Some of the work he did with colleagues to create a congestion control mechanism based on that model has become part of the internet standard and runs on every cable modem in the world. Cisco took the basic mechanism that they developed, adapted it, and pushed it for standardization. “That gives me a big kick,” said Misra. “That algorithm is actually running almost everywhere.”

Since then his research focus has been on networking and now includes work on internet economics. Richard Ma, a former PhD student who is now faculty at National University Singapore, introduced him to this area. They studied network neutrality issues very early on which led to his playing an active part in the net neutrality debate in India, working with the government, regulators, and citizen activists. “India now has the strongest pro-consumer regulations anywhere in the world, which mirrors the definition I proposed of network neutrality,” he said.

For now, he continues research on net neutrality and differential pricing. He is also working on data center networking research with Google, where he is a visiting scientist. Another paper that generalizes the theory of synthetic control and applies the generalized theory to cricket is in the works. The new paper makes a fundamental contribution to the theory of synthetic control and as a fun application, they used it to study cricket.

“While I continue my work in networking, I am really excited about the applications of generalized synthetic control. It is a tool that is going to become incredibly important in all aspects of society,” said Misra. “It can be used in applications from studying the impact of a legislation or policy to algorithmic changes in some system – to predicting cricket scores!”

Find open faculty positions here.

President Bollinger announced that Columbia University along with many other academic institutions (sixteen, including all Ivy League universities) filed an amicus brief in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York challenging the Executive Order regarding immigrants from seven designated countries and refugees. Among other things, the brief asserts that “safety and security concerns can be addressed in a manner that is consistent with the values America has always stood for, including the free flow of ideas and people across borders and the welcoming of immigrants to our universities.”

This recent action provides a moment for us to collectively reflect on our community within Columbia Engineering and the importance of our commitment to maintaining an open and welcoming community for all students, faculty, researchers and administrative staff. As a School of Engineering and Applied Science, we are fortunate to attract students and faculty from diverse backgrounds, from across the country, and from around the world. It is a great benefit to be able to gather engineers and scientists of so many different perspectives and talents – all with a commitment to learning, a focus on pushing the frontiers of knowledge and discovery, and with a passion for translating our work to impact humanity.

I am proud of our community, and wish to take this opportunity to reinforce our collective commitment to maintaining an open and collegial environment. We are fortunate to have the privilege to learn from one another, and to study, work, and live together in such a dynamic and vibrant place as Columbia.

Sincerely,

Mary C. Boyce

Dean of Engineering

Morris A. and Alma Schapiro Professor