Detail

Detail

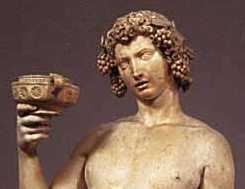

Michelangelo, Buonarroti, 1475-1564.

Bacchus. 1496-1497. Marble. Museo

Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, Italy.

Text Processed for CLiMB Study[From: Hibbard, Howard Michelangelo. 2nd ed. New York : Harper & Row, 1985.] Messer Iacopo Galli, a Roman gentleman of good understanding, made Michelangelo carve a marble <anchor id="1">Bacchus, ten palms in height, in his house; this work in form and bearing in every part corresponds to the description of the ancient writers - his aspect, merry; the eyes, squinting and lascivious, like those of people excessively given to the love of wine. He holds a cup in his right hand, like one about to drink, and looks at it lovingly, taking pleasure in the liquor of which he was the inventor; for this reason he is crowned with a garland of vine leaves. On his left arm he has a tiger's skin, the animal dedicated to him, as one that delights in grapes; and the skin was represented rather than the animal, as Michelangelo desired to signify that he who allows his senses to be overcome by the appetite for that fruit, <pb n="39"> <pb n="40"> <pb n="41"> and the liquor pressed from it, ultimately loses his life. In his left hand he holds a bunch of grapes, which a merry and alert little satyr at his feet furtively enjoys. Michelangelo's first masterpiece [ Vasari, writing about what we would call the transition from Quattrocento to High Renaissance art, emphasizes the beneficial influence of antiquity, citing the newly-discovered 'appeal and vigor of living flesh' and the free attitudes, 'exquisitely graceful and full of movement.' This new spontaneity, 'a grace that simply cannot be measured', and the 'roundness and fullness derived from good judgement and design' are perhaps seen here for the first time in modern sculpture. In addition the statue is novel in its depiction of the god of wine, naked and enraptured with his own sacred fluid. Michelangelo combined familiar ancient proportions with a suspiciously naturalistic rather than ideal nude body. Although several figures of Bacchus survive from antiquity, none is so evocative of the god's mysterious, even androgynous antique character: as Condivi says, it is in the spirit of the ancient writers. Nevertheless, grapes, vine leaves, a wine cup, a skin, and a little satyr can all be found accompanying one or another of the ancient representations. The <anchor

id="1">Bacchus is at first disconcerting.

We imagine the sculptors of antiquity producing noble,

heroic works; when we think of sculpture by Michelangelo,

the David or Moses perhaps spring first to mind [25,

107]. Here we have instead a soft, slightly tipsy

young god, mouth open and eyes rolling [ Jacopo Galli, a banker, was the intimate of a Humanistic circle that included not only Cardinal Riario but also such men as the writer <pb n="42"> Jacopo Sadoleto,

whose dialogue Phaedrus was set in Galli's suburban

villa. We can therefore suspect that Michelangelo

was given learned iconographical information to incorporate

into his statue. The teacher of Bacchus was Silenus,

who was reputed to be the father of the Satyrs. The

flayed skin (probably not a tiger, but perhaps the

legendary leopardus), full of grapes, with its head

between the hooves of the little satyr, must symbolize

life in death. The ancient cults of Dionysus-Bacchus

were associated with wine and revelry but also with

darker things: grisly orgies, ritual sacrifice, the

eating of raw flesh. Some of this veiled frenzy seems

to have been incorporated in the attributes of the

<anchor id="1">Bacchus,

and a sense of mystery filtered down even to the naive

Condivi. In later years Michelangelo returned to the

image of a flayed skin as symbol of his own plight,

both in poetry and in the eerie figure of St Bartholomew

in <anchor id="30">The

Last Judgement [ In a letter of 1 July 1497 Michelangelo wrote his father: Do not be astonished that I have not come back, because I have not yet been able to work out my affairs with the Cardinal, and don't want to leave if I haven't been satisfied and reimbursed for my labor first; with these great personages one has to go slow, since they can't be pushed... This means that the <anchor id="1">Bacchus was finished, but obviously it did not lead to further commissions from Riario, who was not attracted by modern antiquities. A further letter of 19 August reports that I undertook to do a figure for Piero de' Medici and bought marble, and then never began it, because he hasn't done as he promised me. So I'm working on my own and doing a figure for my own pleasure. I bought a piece of marble for five ducats, but it wasn't a good piece and the money was thrown away; then I bought another piece for another five ducats, and this I'm working for my own pleasure. So you must realize that I, too, have expenses and troubles . . . Michelangelo's complaints are made at least partly in response to his father's; the older man was threatened with a lawsuit following his brother's death. But perhaps we can also detect a genuine unhappiness, which Michelangelo could not analyze, and to which he referred in later years: in 1509 he wrote that for twelve years now I have gone about all over Italy, leading a miserable life; I have borne every kind of humiliation, suffered every kind of hardship, worn myself to the bone . . . solely to help my family The choice of 1497 as the year his troubles began is repeated in a letter to his father of 1512: <pb n="43"> I live meanly . . . with the greatest toil and a thousand worries. It has now been about fifteen years since I have had a happy hour; I have done everything to help you, and you have never recognized it or believed it. God pardon us all. We have only the <anchor id="1">Bacchus to show for the block Michelangelo was carving for Riario, for the block he bought and worked for himself, and for the commission from Piero de' Medici. There are records of a standing Cupid (perhaps an Apollo) with arrows and quiver, also done for his friend Jacopo Galli. This statue, described as life-size, with a vase at its foot, has disappeared without a trace.

|

Michelangelo Sample

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The tables below show noun phrases,

keywords, place names, non-place proper names, dates and

related targets (i.e. works) identified in the same sample

by the computational linguistic software tools ("Automated"

column) and by direct human identification of descriptors

("Manual" column). It also shows summary

statistics and calculates "recall" and "precision"

for the automated results. Results are affected, e.g., by lack of specificity as to how noun phrases were to be defined and whether proper names used as modifiers should be consider part of a noun phrase, or as proper names, or both. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||